Something about long-haired, girl-mad boys who insist on bringing their own suits enflames my fancy soul. That isn’t all of what I admire about self-styled dandy Elliott Murphy, but it’s what hooked me when I first caught Aquashow’s cover nearly four decades after it surfaced and disappeared. Murphy wasn’t as weird or effete as I might’ve liked — that’s what John Cale, David Bowie, glam-era Ian Hunter, pre-ambient Eno, Roy Wood, Freddie Mercury (I guess), and the Maels via Muff Winwood (not Tony Visconti, whom Elliott should’ve hired to put a string quartet on Aquashow) are for. Murphy’s tastes and pretensions are indistinguishable sometimes, but he’s more like Bruce without macho, dramatic, or Black leanings, or Dylan if he made friends with Godard (and never shut up about him). Ahhh, but there’s only one of him.

Murphy was a dream interview subject. Back when his Learjet to the top plummeted to earth, he sharpened his hustler’s instinct; he’s been a Parisian exile for ages, but in the age of social media, he’s also always right at your door if you elect to let him and his guitar inside. He was gracious enough to spend some time on the phone with me for the following feature, which I think turned out quite well. Give his records a stream sometime. He fit right into a blue sky time for rock ‘n’ roll — it’s a simple twist of fate he never ended up an American superstar.

“We’re talking about Aquashow, and it’s 2023,” marvels Elliott Murphy, grinning from the couch in his Paris flat. “It’s as close to us now as I was then to The Great Gatsby.”

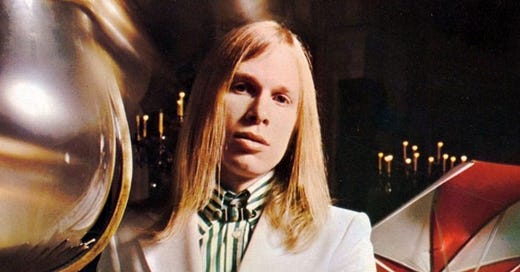

Those bygone ‘20s feel planets apart from the new ones, which don’t roar so much as whine, agonized. The ‘70s scarcely feel closer, and Murphy is one more survivor from the latter. But his is the same wry sneer drawing you in on the cover of his debut – his face has worn so imperceptibly, you wonder about the art collection in his attic. Then there are his twin curtains of luxurious tresses, which glimmered like spun gold down his alabaster suit in the Aquashow shot. If he’s thinning at the top, it’s concealed by a baseball cap, an unusually casual choice for a head better-suited to fancier chapeaus.

There’s a painting of Murphy behind him, by Richard Sassin, who was close enough to David Hockney to earn his own portrait. “So it’s not a portrait by David Hockney, but a portrait by a guy who had his portrait painted by Hockney,” he clarifies with pride.

Murphy is always ready with a name-drop — when I mention Don’t Look Back, he tells me he was just on the phone with Paula Batson, former lover of Bobby Neuwirth. He’ll cite the far less productive Billy Joel, who inducted Elliott into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame. Or John Prine, who’d proposed a joint tour backstage at Prine’s last-ever show before his death from COVID. Or “Bruce”, you know the one, a longtime friend and at one time Murphy’s closest rival — and an on-record fan of his “beautiful hair.”

Much has been made of the symbiosis between Springsteen and Murphy, and not only by Murphy himself. The two performers hit at the same time, from roughly the same area, and in the exact same way. Both were beneficiaries of an expanding rock scene, its floodgates open to an ocean of restless young dudes armed with affordable guitars and impossible dreams. While Bruce favored energetic polyrhythms, and preoccupied himself with the plight of the heartland striver, Murphy’s proclivities were loftier and more involuted. His rock ‘n’ roll touchstones were Blonde on Blonde, the Dylan LP on which the former scion of protest-folk went full pop art, and Loaded, the Velvets LP on which deathly ironic English major Lou Reed pretended, at least, to go full pop.

Both Murphy and Springsteen invited frequent Dylan comparisons upon arrival. See, Fifty years ago, Dylan was still a legendary recluse, whose retreat had left the scene smarting, and starving for another cerebral superstar. Thus arrived a new wave touted thirstily by proselytized critics as heirs to their jester’s thorny crown. “If you go back and listen to all of the New Dylans,” Murphy muses, “me, Bruce, John Prine, Loudon Wainwright — none of us really sound like Dylan. Or sound like each other. At all!”

What united these artists was a love of literature and lust for language, in the manner Dylan had pioneered. “He opened the door for all of us. ‘The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face.’ All of a sudden it’s like, this is Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg. Or ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’ — ‘you’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books’ — which I have. That was the terre commune. We were writing short stories — very short stories — to music.” The folk ballads which were Dylan’s Trojan horse were similarly influential, more verbally satisfying than the wop-bop-a-loo-bop of rock’ ‘n roll. “But I was not James Taylor. I was always a rocker, you know? I was a singer-songwriter, but I wasn’t coming in with an acoustic guitar, I was coming with a Fender Stratocaster.”

Where the arc of Murphy’s career evokes Dylan’s is where it also evokes the hero of his all-time favorite novel. Like Robert Zimmerman and James Gatz, Murphy’s youth was spent in the willful pursuit of a north star vision of his own true identity, from a zealous yearning for something much bigger. “When you’re a kid stuck in the suburbs playing your guitar, [stardom] just seems like Mount Olympus with Zeus,” he observes. “It’s unapproachable, unattainable. But you still have dreams of it.” Unlike Dylan and Gatsby, Murphy felt no urge to change his name, which he shared with his father. The elder Elliott ran, surprise!, an aquashow — a choreographed extravaganza beginning its triumphant run in 1946, at the site of the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows.

At its peak, the show roped in the Jazz Age’s brightest light, Duke Ellington himself (it’s not clear if Ellington got wet). Murphy Sr. soon became a restauranteur, opening the Sky Club, frequented in its heyday by Kennedys and Rockefellers. But shortly after his Aquashow’s reappearance at the ’64 World’s Fair, Elliott’s father suddenly passed away. Unable to sustain their lavish lifestyle, the family moved out of their mansion. The teenage Elliott was suddenly just another Long Island kid with the white middle-class blues. By ‘71, “there was just nothing happening for me. I was just at community college, taking literature courses.” No fool, he nevertheless knew he’d feel far more at home somewhere angels feared to tread. It was time for his own showstopping feat.

Murphy’s appetite for adventure was stoked by his friend Rory Calhoun. He wasn’t the ‘50s heartthrob, but his brother was dating one: Farley Granger. The couple lived out in Rome, and Calhoun invited Murphy on a visit. Stars aligned to make this possible. “I’d missed the Summer of Love in San Francisco, but that ambience was still kind of happening in Amsterdam, and I had friends over there. My sister was a stewardess for Pan Am, so she could get me a ticket for like, nothing.” Elliott left, not looking back. “Once I landed at that airport, it’s like all the grief from my father’s death just left me. The old world became my new world. That trip is probably the reason I’m still here today. Everything just kind of fell into place, from Amsterdam to Brussels to Paris.”

There was no set itinerary. Granger suggested Murphy and Calhoun head down to the Cinecittà studio, where Fellini was filming Roma. “So I basically worked as a glorified extra for Fellini for a week.” His European excursion was dotted with casually magic episodes like this, including helping a girlfriend escape from her Swiss private school by midnight rowboat. But Murphy couldn’t outrun American pop. “I [met] this bunch of people in Rome; they were like international hippies. They knew the Rolling Stones and people like that. And they told me — if you go back to NYC, you’ve gotta hang out at Max’s Kansas City.” A regular recent refuge for New York School artists and Andy Warhol superstars, the club had become the epicenter of a piquant new flavor of chic.

He flew back to the States via San Francisco, but ended right back up in Garden City. So he turned the two-bedroom he’d escaped into a rehearsal space for a new band, his brother Matthew its bassist. Soon they were banging around the Big Apple, booking gigs at fabled spots like the Mercer Arts Center, Kenny’s Castaways, the Bitter End, and Max’s Kansas City. The European interlude proved crucial: “If I would’ve gone in as a kid from Long Island, it never would have worked. There’s that prejudice against the bridge and tunnel crowd from the true Manhattanites. But when I went back and started hanging out, just an elegant expat hippie in European clothes, I fit right in.”

After wearing their knuckles down knocking on doors for a deal, Murphy and his new group lucked into a walk-in audition for Polydor Records. “The receptionist says ‘can I help you?’ We say ‘yes, we have a demo we’d like you to listen to’. She says, ‘when?’ I said ‘now’. So she called up a woman called Shelley Snow. I guess we looked good — we were dressed in King’s Road, swinging London garb. She brought us back, played it, liked it, and said, ‘can you come into a rehearsal studio and audition for the head of the A&R?’, who was Peter Siegel. It was just him and Shelly on folding chairs. And they said, ‘OK, you’ve got a deal if you want it.’” He shakes his head recalling all this. “It would never happen like this today. It wouldn’t have happened five years later.”

Murphy quickly found himself strategically dodging the clinch of the industry’s gears. “The first bomb was that they didn’t want to sign the band. They just wanted to sign me and my brother. And the band didn’t like that, of course. But we had tried so many labels, what could I do?” The next was assigning producer Thomas Jefferson Kaye, a journeyman label executive and songwriter who’d helmed Loudon Wainwright’s fluke hit “Dead Skunk”. But Murphy smelled something amiss not long after landing in LA to begin recording. “He wanted to turn me into a country-rocker,” he says, singing a loping, drawling snatch of “Last of the Rock Stars” to illustrate this evaded horror.

At a crossroads, Murphy and his band retreated one night to celebrity hangout the Rainbow. Murphy put his elbow on his booth, brushing the figure behind him. He turned to face him, finding himself nose to nose with Bob Dylan. Murphy saw this chance encounter as a sign, and the next morning, he insisted to Polydor he fly back and do his debut in New York City. Isn’t this a glorious bit of fabulism, I ask — pure Dylanesque copy? “Absolutely true,” Murphy declares. “We got out of there quickly, and we tried to follow him — he had a baby blue station wagon. But we lost him”.

They resumed work at the Record Plant. “Peter Siegel had decided that he’d produce it himself — he signed the deal, he’d better make it happen. We could only record at night, because he was working during the day. We were on the top floor, and below us were the New York Dolls, doing their second album. I would visit them on breaks, and it was like a Roman orgy going on down there. But when you went up to our session, it was like a Quaker prayer meeting!” Pared down to the core of Elliott, Matthew, and stalwart sessioneers Frank Owens (piano and organ), Teddy Irwin (guitar), and Gene Parsons (drums), the sound was brisk, tight, and spare, flawlessly tailored to the songs.

Murphy’s music evoked the brittle rush of ’65-6 Dylan and the city-hardened pop of Loaded, but it was breezier, warmer, smarmier. It had a sense of victory you weren’t sure was earned, but sounded too convincing to doubt, to not get swept up in too. His diction was pugnacious and his timbre callow — one more Jagger-ignited non-singer ready to hector you directly from the center of his lilywhite soul. Yet Murphy could also sound full of hope, with an air of faith you were in on his joke too. He could be sarcastic without being nasty; his rhymes’ allusive twists put a felt tip on his sharpest barbs. Sheer passion for words and music sparkles through and lights up Aquashow.

It opens with a memorably oblique double-entendre — “naked telephone poles can’t describe the way I’m feeling ‘bout you tonight” — but soon settles into a landscape of terrific lines. Surveying a scene that stretches from the suburbs to the city, Murphy winds between a cocksure certainty he’ll rise above his hometown and a weary terror he’ll never escape it. Like Dylan, the lyrics mostly address obscure objects of desire — he’s got them in a corner, but they’ve got him in their pocket. Beaming over the stage he sets is the distant beacon of pop fame and fortune, a future less surefire than it was in years before, yet the only fire in Murphy’s heart (or under his ass) he can count on.

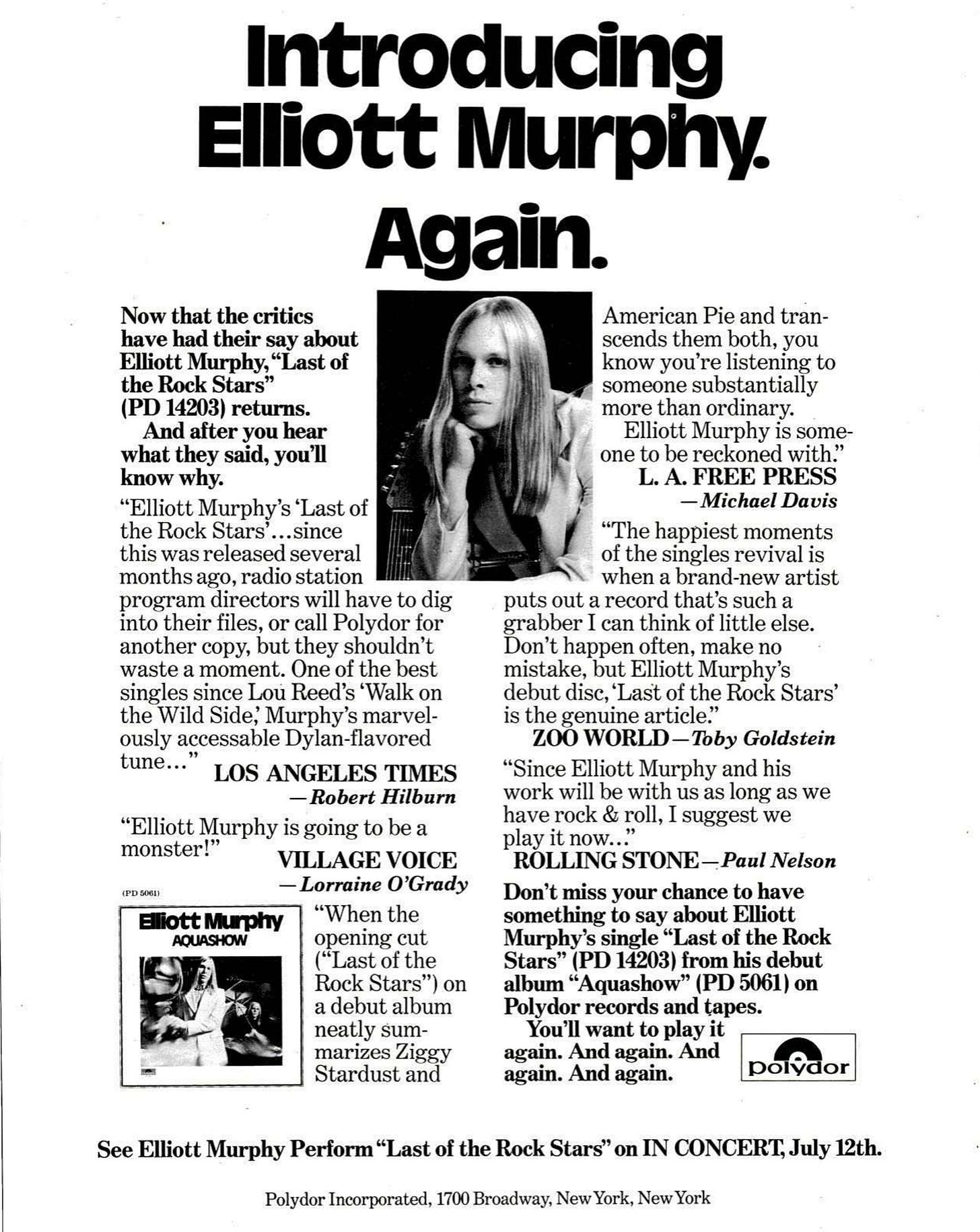

Aquashow came out at year’s end, a minnow in a sea of whale-sized blockbusters — Elton John’s extravaganza Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, the Who’s latest magnum opus Quadrophenia, and Ringo’s self-titled, star-studded shot at solo glory. “[Polydor] really didn’t know what they had,” Murphy recalls, and copies languished in the racks. Then Paul Nelson, both a Rolling Stone critic and the A&R man who’d signed the New York Dolls to Mercury, stepped in. “He’s the best Dylan since 1968,” Nelson declared, in a January ‘74 rave in Rolling Stone. “For someone who sounds as if he invented his life from Twenties novels, Murphy in person is a likable, totally believable, extraordinarily intelligent young man who seems caught in the shadow world of the potential teenage tragic hero and the gates-of-Eden, strawberry-fields, no-expectations land of the true gods of rock & roll. It’s nice work, if you can get it.” Nelson knew from living myths.

“When he wrote that, [it] just started the ball rolling,” Murphy says. “You could really say my career began at the moment that I was discovered by the critics”. Aquashow’s press packet is something to behold, an omnibus of breathless testimonials from all the rockcrit luminaries. “Elliott Murphy doesn’t need to demand attention when he enters a room; he just walks in, and he’s got it,” marveled Dave Marsh. “He is certainly the best thing to happen to the New York scene since the Dolls,” declared Ellen Willis. Robert Christgau gave the album an A: “he does know quite a bit… the quick phrases shield a plausible sincerity”. “[He]’s going to be a monster”, predicted the Village Voice.

But despite that cavalcade of effusions, Aquashow wasn’t a hit — it didn’t even make the album charts. Hot off a promising miss, the coyer-than-tough Murphy was poised for an increasingly less adventurous industry to sand down his rougher edges. A genre-defiant singer-songwriter whose verbal and melodic nuances were his primary selling points needed sympathetic tending. But Polydor had a bad rap, and Aquashow’s failure seemed to discredit Peter Siegel. So Lou Reed, now Elliott’s friend, helped hook him up with RCA. But a drug bust kept him from producing the next LP, Lost Generation.

Years after his impulsive LA exodus, Murphy found himself back in the city of angels, with Doors producer Paul Rothchild. “Paul put together this superstar session band, which at some point was a little overwhelming for the songs.” Though its material is often potent, Lost Generation feels embalmed. Meanwhile, an old rival had found the perfect producer for the sounds in his soul. “In 1973 and 1974, it seemed to many of us that it was a tossup whether Bruce Springsteen or Elliott Murphy would become a national hero first,” wrote Dave Marsh in 1976. “We all know how that turned out.”

Murphy released just two more LPs on a major label — 1976’s Night Lights and 1977’s Just a Story from America. But by 1980, he was out of both fashion and a contract. Yet he great last turn in his career was soon to come. “When I first played Paris, I’d been dropped by Columbia and didn’t know what to do. But I was sold out, and there were six encores. And I said, ooh, maybe there is a second act that can happen.” He settled in the city, where he’s lived and worked ever since. A peace now beams off his face.

Like Springsteen, whom he’s joined on stage several times, the thrill of the next show sustains Murphy. He continues to release excellent albums, many produced by his son Gaspard — among the best of them a haunting revisitation of that first LP, Aquashow Deconstructed. Not that Murphy is above a bit of grousing. “I was talking to [Gaspard] the other day — moaning about how I never really had a big hit record. And he said, well Dad, I think a career of over fifty years is something like a hit record!” C’est vrai.

Some dreamers rise to the top only to be thrown from their motorcycles, or shot dead in their swimming pools. But not Elliott Murphy — half a century after his opening bow, he’s alive and well and living in Paris, and still dreaming of his next big move.