My honorary sister, blood of my Paul, obliged me two weeks ago with her stab at how one would explain the Beatles to someone somehow out of the loop. It’s as well-turned (and comprehensive, and cheeky) as her writing typically is. Fonder for even longer of a band everyone likes to assume is my favorite (it isn’t), I can think of very few people more qualified to write a 500-page Beatle fanfic – and her work itself transcends that category beyond even my high expectations. I can’t simply repost what Megan wrote, though she did better than I’ve managed all month (however much is my own lack of trying, or time to try). But ask her about the Beatles sometime. You’ll be in for a treat.

Still, since this is my blog, and my last Beatles post before slowly endeavoring to peel Apple in a way no extant text on the matter strikes me as having necessarily achieved, I ought to give it one more go, before I make my way through the two dozen songs of the Fab Four’s richest, strangest, most harmonious and consequential recording year. And since I’m desperate for parameters or a compass on this subject, I’m going to use (the polite way of saying “steal”) Megan’s framework as a rough template. (Hi Megan!) That said, I have to cite her subtitle: the Beatles “broke music’s brain”– and ours, too.

Many including myself have mentioned the right-place-right-time factor. The Beatles could’ve only happened in the sixties, conceivably can only have been white men given the harsh strictures of the time (and, you know, this one), could maybe have only been English speakers, absolutely needed to defy standards of masculinity and hair length (“questionable,” Megan calls said style, though it’s the one haircut in my life I’ve never questioned), definitely needed to be a collective rather than Johnny & the Moondogs. They needed Brian Epstein and George Martin and Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans and Derek Taylor and Pete Best and Billy Preston and Harry Nilsson and Yoko Ono, if not at all in the way all of them needed the Beatles. They needed every screaming teenage girl and every twentysomething boy who grew out his locks and got too serious about himself, for the numbers if not individually. They needed all that money and power, if not from a philosophical perspective, to make the music they made how they made it.

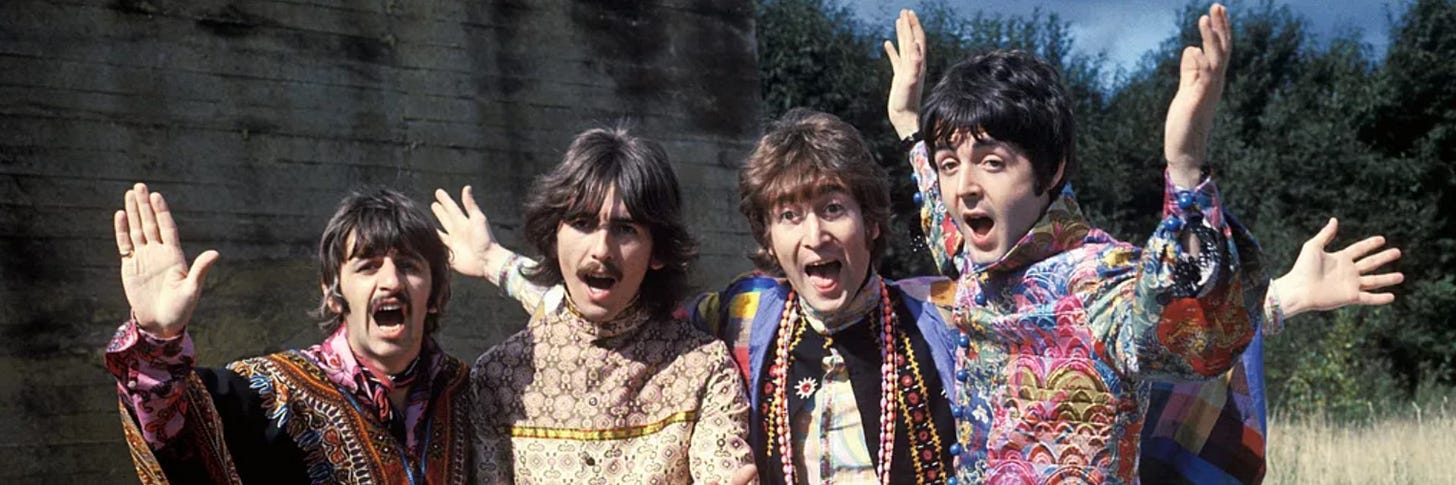

They needed to be different, than each other and than any previous historical figure. John needed his acid wit and sweet pain (per Megan: “the poetic rebel who scribbled existential zingers”), Paul needed to be corny, charismatic and calculated (“[a] human sunbeam, with smooth bass chops and a voice that glides like butter”), George needed to somehow be everything those two weren’t (“the quiet mystic… introduced the sitar and low-key wrote bangers”), Ringo needed to feel like anybody could be up there in his place even if only Ringo could (“drummer with a heart of gold and a ‘just happy to be here’ vibe”). They needed to write a lot better than the competition, without having studied how to. They all needed to be sexy in a way that defied the existing standards.

Megan attempts to break down the elements; like me, I think it lightly itches her how many of these remarkable facts have become clichés. All popular artists, all artists in a way, pay tribute to the modes they revered by reconstituting them, or just balling it all up and infusing personality, verve, talent, whatever’s on hand. Something about their historical moment – Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry and others’ tying together strands the charts still literally divided (pop = anodyne, country = poor white, R&B = Black), the “pop art” prism they may only have been so conscious of but which made their art self-conscious in the best way, the mechanization that defined dominant ‘50s music… the way the Beatles’ music was secondhand and felt firsthand was crucial to its impact.

They mercilessly blended genres, less devoted to individual traditions than Presley or Berry, and by the time of the White Album you can hear them inventing them too. It ties into their studio prowess, which wasn’t prowess so much as curiosity and 10,000 hours (the actual number is out there somewhere, or we can just ask Mark Lewisohn). They didn’t invent the Studio As Instrument, but they perfected it, and again, in a way so dependent on all that accumulated money and power – which also accounts for how they accomplished and influenced so much in only seven years. Every recording made in the ‘70s is informed by their music; almost all of what came after starts in the ‘70s. You can’t credit them for everything, and you can call their ardor for pop music theft (it’s become quite fashionable), but the proof is the tree rings in the historical record.

Megan calls their songwriting “unfairly good”, and that’s true – those ingenious early songs I’ve covered in the previous entries often feel like luck and epiphany as much as skill and wild gift. Paul could write the “swoony melodies”, but so could John (“Julia”), and while Paul wasn’t “introspective” in the same way, he could sure do raw (“Helter Skelter”), and sometimes found emotional truths a good deal less foolish than (if just as ill-defined as) John’s I-think-I-know-I-mean-oh-yes – recall “For No One” or “I’m Looking Through You” or something as satisfied as “Here There and Everywhere” (he was, it seems, the one who worked out that thing that’s all you need, post-Linda bunts notwithstanding). But of course no walls ever fully separated the pair – they loved, and admired, each other more than boys were supposed to, and got each other more than any future partner could hope to. Their collaboration was, yes Megan, “pure magic”.

There was of course another songwriter in the band (technically two), and she refers to George’s “late-game glow-up”. I’ve always seen “Something” and GH’s other wins, and I think you can count them on three hands, as the result of the same letting-someone-wander-in-wonderland process by which we got a record that sounds like Revolver. For a simple, impressionable, and moody fellow, George had just enough edge to his razor wit to know a thing or two, and to rise above the room with a quip or judicious silence when he gauged the scene. He saw himself as the guitarist in a Clapton-shaped game who “plays what’s left”, and he was possibly pop’s most rewarding fashioner of totally nonsensical chord combos. Surely those techniques got under McCartney’s skin, but while Paul still hangs onto the industry for dear life, Harrison turned his back on any terms but his own. Through spiritual conviction, he made an untimely end feel timely.

And then there’s Ringo, and every great friend group has a Ringo – a person of such benevolence, humility and good cheer home feels like home when strife is afoot and tensions are highest. He wrote too, and at his finest, made self-effacement a kind of high art; that last verse of “Early 1970” beats any of his mates’ contemporary singles.

There’s more, always more – “cultural cheat code”, “media geniuses”, and “legacy flex” fill out Megan’s list, and who can say what’s missing from the things we’ve said today. (Probably any of you reading this!) But for sure, and flattering those who seem to be annoyed at having to give these four problematic museum pieces credit, the Beatles were more than just a band. The band included their audience, influences, context and of course those sparks and happy accidents in the spaces between all these things. But as I’ve said already, the records are the record, and on “Strawberry Fields Forever” you don’t hear audience or history or even what sounds like a rock band. You hear sound and vision. None of it should be as transcendent as it remains. But yes it is – it’s true.

STRAWBERRY FIELDS FOREVER (A-side, R 5570, 2/17/67)

They found a space at the edges of rock which acknowledged it was all just modern sound – electricity and effects – and affirmed that those tools could be used to evoke a dream better than any other medium. “A dream” is subjective anyway, but the point is this isn’t – it’s universally recognizable as a reverie, with a tart hint of cranberry sauce.

PENNY LANE (A-side, R 5570, 2/17/67)

One of my favorite Lennon-v.-McCartney analyses is that Paul saw LSD as “vaudeville for the mind”, whereas John nearly destroyed himself trying to figure it all out on it. “Strawberry Fields” untangles mental knots, finding profundity without defining it; this unfurls a vibrant tapestry of local color, its profundity in 100 heavenly melodies.

SGT. PEPPER’S LONELY HEARTS CLUB BAND (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

The first “event album” in a long line down to Beyoncé begins with the semi-hushed murmur of a crowd. Then the band slams in, stiffer and perhaps archer than the boys from the cavern, but still socking it pretty good. Recorded on a 4-track, an LP many recall as expansive and ornate is actually quite spare, the best kind of special effect.

WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

Permanently friendly – he lost his yawp with his tonsils – two of Ringo’s friends locate his perfect context, both tempering and strengthening swing and sentiment alike. The melody is fetching and quietly fantastic, but at the song’s luminous core is a feeling as complex as “Strawberry Fields” and utopian-openhearted as “All You Need is Love”.

LUCY IN THE SKY WITH DIAMONDS (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

With its crystalline Lowrey and wash of tambura, this suits – and underpins – the only theme of this non-concept album, which is a pervasive, unbound and (that word again) kaleidoscopic sense of wonder, Paul’s joyous harmony the fruit atop your third round of pavlova. It isn’t really about acid, but its agape and blurred reality aren’t unrelated.

GETTING BETTER (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

Kicking off with staccato stabs of sunshine, this raves up a music-hall beat, but looks forward in ways you wonder if it fully realizes. The radical positivity is a lot punchier than the sweet/sour rejoinders, and few on-the-record spousal batterers (all of them at least dabbled in this) wrote gorgeous bridges about feeling really remorseful about it.

FIXING A HOLE (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

Nobody concocted theme songs for dandy fops more fluently than Paul. But the lyrical vibe is the flip, fraternal-if-antisocial libertarianism of an affluent genius holed up on a farm, writing the greatest album ever (it isn’t, but it invented the concept). Yet again the arrangement is an austere counterpoint, and yet again the melody is unbelievable.

SHE’S LEAVING HOME (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

Richard Hewson was a less corny arranger than George Martin, but today I heard this former favorite as tinged with saccharine (not like it’s a Lennon song). What makes it work – besides being really beautiful – is the narrator’s empathy, that old “She Loves You” trick, not just for his blithe-spirit subject but a mom born into a different world.

BEING FOR THE BENEFIT OF MR. KITE! (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

It’s a testament to Lennon’s eternal and inimitable charisma that – agonizing out four songs in a drug-hangover slog, and so foggy he has to steal lyrics from a circus poster that was just what, lying around? – he manages to come off both seductively debonair (move over Joel Grey) and acidic-apathetic (meaning punk). The fun kind of bad dream.

WITHIN YOU WITHOUT YOU (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

This really works – where “Love You To” is for Velvet Underground fans, this could peace out and/or stimulate people who only listen to musicals. The aimless-sourpuss lyrics make me wonder how much of its prowess is just musical, and how much that has to do with the innate sound of the instruments. But it’s still one of George’s best.

WHEN I’M SIXTY-FOUR (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

Between Harrison’s most hypnotic dirge and Lennon’s sharpest suburban protest song are two tracks where Macca really wants to sell you a pair of epaulets, the ones where you can hear the seeds of the impatience “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” brought out in the other three. But he couldn’t ruin a melody if he tried. We all hope to sing it at 64.

LOVELY RITA (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

Insistence that “Good Morning Good Morning” is the weakest song on the Greatest Album is incorrect. It’s relatively indifferent (Paul is noticeably flat on some of notes) and casually silly in a strawberry field of enlightened semi-sense, the joke if there is one that a lady is in a position of authority, a tacked-on dream-devolution for a coda.

GOOD MORNING GOOD MORNING (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

These titles are perfect; the lack of punctuation here, the presence of it in “Mr. Kite!”, the 19 words total in the first three. A rooster-rude blare of brass, miked horribly like they liked it, fleshes out the bitterest (and most incisive) lyric on the album – but it’s a breakfast of champions, melody sweet as cream and chopped-up rhythms très piquant.

SGT. PEPPER’S… (REPRISE) (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

In 1:19, they officialize their latest pop album as a symphony or something, though it’s the hardest track on the album. It restores to full force that dreamlike feeling the last few cuts reigned in a little – I’d have loved to pick George Martin’s brain on how this was conceived and created. It’s also the only time on Pepper Ringo sounds like a boss.

A DAY IN THE LIFE (Sgt. Pepper’s…, PCS 7027, 6/1/67)

As vinyl dreams (or nightmares) go, it’s not as concise or self-contained as “Strawberry Fields” (or “I Am the Walrus”), but it’s still yet another master class in dissolving form in vision. John was scary in other ways on Apple, but here, thinning his voice through an alien filter, he’s eeriness defined, and Paul’s section proves their enduring synergy.

ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE (A-side, R 5620, 7/7/67)

You could mistake it for corny from miles away, or with your head in the sand. But it’s not some bullshit valentine, it’s the climax of a broadcast designed with, as Ringo put it, “peace and bloody love” in mind: actually, sincerely, and not a single speck stupidly. One of John’s loveliest melodies and lyrics, its coup not only its brilliant arrangement.

BABY YOU’RE A RICH MAN (B-side, R 5620, 7/7/67)

The trouble with drugs is they wear off. Here we hear a verse melody so remarkable it could’ve only been written by the Fabs in ‘67 stuck in a smear of rainbow fudge with a pedestrian chorus. There’s a worthy concept in sight, “Taxman” turning on itself. But the most interesting thing about it is that they could be singing “rich f*g J*w” at Brian.

HELLO GOODBYE (A-side, R 5655, 11/24/67)

Where “Penny Lane” feels decidedly like the K2 to “Strawberry Fields”’ Everest, this is the most absolutely Paul proved the power of his own positivity, not “Walrus”’ inferior but its soulmate if not twin flame. Its outreach matches their last single, its agape the last LP, its scope and depth the music on the other side. Heaven on Earth, with cellos.

I AM THE WALRUS (B-side, R 5655, 11/24/67)

The hardest thing about writing this entry, most of these in fact, is the hardest thing about writing about the Beatles – finding superlatives to burst the superlatives, which is why I’m favoring equivalents to throwing my hands up. I know the Fabs so well, I’m rarely surprised anymore. But with this and “Strawberry Fields”, I’m perpetually rapt.

MAGICAL MYSTERY TOUR (Magical Mystery Tour, SMMT 1, 12/8/67)

The trouble with drugs is they don’t exactly mix with discipline, which you really need once the fresh inspiration and wide-eyed wonder start to run out (more drugs does not help). Their worst film needed more than a “scrupt”, and this cute, sometimes rousing ditty spends its space fumbling for what Pepper’s title track nails with efficient savvy.

YOUR MOTHER SHOULD KNOW (Magical Mystery Tour, SMMT 1, 12/8/67)

Another song that sounds like you’re dreaming it while it’s happening, and though it sees McCartney inching ever closer to pastiche and nonsense, the melody is insanely alluring. We’re still in a milieu so revolutionary it makes “Things We Said Today” feel like a half-engaged exercise in major-minor, though the lyrics mean a good deal less.

BLUE JAY WAY (Magical Mystery Tour, SMMT 1, 12/8/67)

As George dirges go, where “Within You Without You” feels stately and accomplished this really does feel at its weakest like you’re stuck in someone else’s hangover. It does capture something sad and amusing, in a way, about the lifestyles of this brand of rich and famous. And they still did dreamlike better than a thousand psychedelic imitators.

THE FOOL ON THE HILL (Magical Mystery Tour, SMMT 1, 12/8/67)

At the time, Robert Christgau called this the worst song Paul had written to date, and while it’s more whimsical and less self-convinced than “I Am a Rock”, it’s also not as probing, desperate, or good a pop song. He really checks out on that last verse (“they don’t like him” yeah we know), but once again his melodic sense rushes to the rescue.

FLYING (Magical Mystery Tour, SMMT 1, 12/8/67)

If we can shatter superlatives trying vainly to trap their genius in words, we can knock them for mellotron pastorales the Moody Blues would leave on the cutting room floor. The whole of Mystery Tour is just princes fooling around, because for five years letting the world follow their whims had proven mutually beneficial beyond all imagination.

LADY MADONNA (A-side, R 5675, 3/15/68)

Here’s a first preview of the stylistic aimlessness that followed their chemically-aided ascension toward high art’s peak – where, as Prince reported, “there’s nothing there”. While the Stones shook off 1967 with roughness and force, this attempts to hang onto the whimsy of psychedelia without the wonder. It rocks and annoys you in equal parts.

THE INNER LIGHT (B-side, R 5675, 3/15/68)

Ellen Willis opined that the Beatles first faltered when George got into India; she was onto something key. Their best nonmusical gifts were for subversion and humor, their sincerity channeled into love for a world of musical rebels. This is hypnotic, daybreak after a deep blue dream. But though it’s entirely serious, it might also be meaningless.

And where was Brian in all this music? Why did they falter so utterly after five years of not just never missing steps, but taking every one of them up a stairway to heaven? It serves to verify something that, itself, uneasily verifies the impermanence indelible to the life experience. It wasn’t just four inexhaustible fountains of talent. It was chance and chemistry, culture and circumstance, the kind of confluence less dependable than planetary alignment. A dialogue with the audience, with constraints, with cohorts and each other. It is scientifically and anthropologically explicable. But it’s also a miracle – the greatest story ever told, featuring the greatest soundtrack ever recorded*. And that story’s epic epilogue is so conversely unromantic, it doesn’t even end in tears. Mostly.

*maybe

Ryan, oh my god— my cheeks are legit burning right now 🥴. Your words? So dang sweet, they could’ve been plucked from a McCartney love song—though I know you’re more of a Lennon wit kinda guy. Honestly, when I threw those random thoughts out, I never expected them to leave my notebook, let alone end up in your ridiculously sharp breakdown. But hey, when have the Fab Four ever followed the usual rules? 🤷♀️

Diving into your analysis was next-level. Seriously, it was like watching someone decode "I Am the Walrus" with the brain of a philosophy professor and the heart of a die-hard fan ❤️. You nailed the magic of it all—the wild chaos, the unshakable bond, the sheer cosmic luck that brought them together. (Also, “blood of my Paul”... Thank you for the Tim shout out and I adore being referred to that way.)

Huge thanks for the shout-out, man. It means the world to find another soul who truly gets why I call them “my boys” like they’re old friends ✨. Your writing about them bursts with so much love and respect—it’s downright contagious. We have to sit down soon and geek out properly... (And yes, I know I still owe you my For Sale thoughts—this week got away from me, but it’s coming, I promise!)