This morning, the increasingly reflective (he’s 83, after all) Robert Christgau pulled a famous misfire by his favorite Fab fourth off the shelf and got nostalgic. It’s possible that sometimes the irretrievability of bygone history raises its value. I’m not usually in the business of deeply disagreeing with our Dean. But I believe he was right the first time, for reasons I detailed in this piece I wrote for the Globe in February, and have retouched a bit. (At the time I was proud that, for all the words I included, I omitted one — rhymes with Cheadle). Indeed, the issue is still “mysteries of emotional and rhythmic commitment”, if not quite so mysterious anymore.

John Lennon was a war baby — his middle name was Winston, for God’s sake. And unlike many of his boomer peers, he carried a shrapnel-shard of endless battle in his head like a pearl. He wanted to empower people into giving peace a chance, but when he felt his passion hardest, it resembled rage, however righteous. Listen to those soul covers on his group’s first LPs: he transforms the impatience of “Please Mr. Postman”, the frustration of “Money (That’s What I Want)”, the devotion of “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me”, the resignation of “Anna”, and the chaotic joy of “Twist and Shout” into something fiery and a little frightening. When Paul tears into “Long Tall Sally”, he’s burning up pavement in his sports car, but you’re never worried he’s going to crash.

Ahh, but John was the original crashout queen. And when he blew up the institution he rose to fame (and power) on, with Guy Fawkes levels of strategy and remorse, he seemed the best equipped of his quartet to capitalize, or something lefter-wing than that. Sure, nobody asked for the “experimental” LPs he prematurely kicked off a solo career with, the most listenable of which deterred the curious coming clad in naked photos of himself and the spark at his inborn avant-garde tinder, one Yoko Ono. But with his intellect-signaling spectacles, wisdom-signaling beard, guru-white wardrobe, and barely-shaken status as Leader of the Finest Band, his exhortations to pacifistic revolution carried a credence they might not have from many other fortunate sons.

But even fans of the original (and best) “Revolution” noted that John seemed unready to put his money, or anything else, where his mouth was. Only one cause stirred the courage of his contagious convictions in the man himself: the man himself. In a long, wintry year of myth-dismantling solo albums — with Paul phoning it in, Ringo trying on hats, and George burning down his boundaries — the final entry, and first Lennon LP EMI deemed unalienating enough to merit a non-vanity catalog number, featured our hero decrying God Herself, and shrieking out all his unvarnished pain in a manner that made “Money” feel “Summertime Blues”-level petulant. Plastic Ono Band was a private revolution. And while it was brave, it was too personal to start a movement.

Lennon was thrilling when he lost his cool (“Help!”, “Yer Blues”, the now-unlistenable “Run for Your Life”), but rarely shrewd, no matter how many of those vocals he aced. Hence the bridge-burning Lennon Remembers interview, which resulted in a National Lampoon parody, “Magical Misery Tour” (“GENIUS IS PAAAAIIIINNNN”). But he still had pop instincts worthy of his glasses ca. ‘71, noting in a drunk-dial of an open letter to Paul that a coarse, forthright social commentary like “Working Class Hero” could use a spoonful of the sugar in which his old estranged fiancé reliably coated his bullshit. “Jealous Guy” and “Gimme Some Truth” aren’t less personal or political than “Mother” or “Give Peace a Chance”. Yet they boast the same preternatural instincts of the man who co-wrote “I Want to Hold Your Hand”, and for the final time on record.

But who knows what happened in 1972 — show me the U.S. electoral map that year and I’ll show you a conspiratorial mystery they’ll never declassify. Lennon, the Fabs’ sole permanent U.S. resident at the time, wasn’t just shouldering an outsized fourth of the band’s unprecedented fame, which even Ringo was drinking his weeks away over. Lennon’s mouth almighty, his not-so-secret weapon and own worst enemy, drew the paranoid focus of the first US President (maybe) to draft an enemies list, thus giving John’s own copious paranoia some legitimacy. His only release that election year was the charmless Some Time in New York City — one disc of agitprop-pop featuring Yoko’s crude first stabs at hooks, and a jamming-with-Frank disc which made “Apple Jam” taste like caviar. Its sole good song was keyed to an unapologetic use of the n-word.

All that money never ended up buying John effective therapy (still in development then, of course) or, God knows, medication. But it was his wild will that brought his old band to their massive success in the first place, and pulled them into transcendent iconoclast corners like “I Am the Walrus” after their drug use had ripened into kandy-kolored whimsy. In 1968, manic-depressive strokes like “Glass Onion,” “Revolution,” “Yer Blues,” and “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” are why “Lady Madonna” didn’t have to beat “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”. And try to imagine Abbey Road sans “Come Together” or “I Want You” without getting a toothache. Still, as his band folded, his poorly-policed personal life yielded missteps (“Cold Turkey”, “Power to the People”). His winning wit had given way to a drug-warped sincerity.

So John wasn’t prepared to deal with the landslide loss of the anti-Nixon candidate he’d worked so… well, inconsistently and lazily, but intently, to help win. His method of coping was one entitlement two-step too far: he had sex with another woman at the election party, with Yoko close enough to hear every torturous sound from outside the door. She herself had been working hard (if, again, not for McGovern) since Some Time in New York City, preparing a double album of songs that, while often awkward and secondhand, were sometimes not just as good but as groundbreaking as John’s latest best. We know from Paul that John wasn’t just a jealous guy about romance; all he’d written recently was “Nutopian International Anthem,” and not even the title. Yoko was about to serve John his slice of piss-off cake — and he couldn’t even eat it, too.

Now, not every compulsively self-destructive romantic exile gets a live-in replacement companion specially selected by your toxic bullshit’s victim (enter the ever-intriguing May Pang, who it sometimes seems might have been a better match for Lennon if he’d only gotten over himself, and who suffered abuse not just from John but Yoko). Nor to be able to spend ungodly amounts of money on brandy alexanders with Harry Nilsson, not to mention studio time (occasionally with Paul McCartney on hand!) you’re apt to waste on cocaine you didn’t get for free either. At his vocal weakest — like Dylan and Bowie, who also had a tough time with fame, John destroyed his voice in the ‘70s — the Fabs’ best singer sounded like a Looney Tunes character after a sobbing binge.

The pain throughout Mind Games and Walls and Bridges, the work of a great artist not conceding but stumbling backward into contemporary trends (cf. Goats Head Soup and It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll, which also can’t decide if they’re slick or a mess), isn’t the genius kind. The melodies are his most rote (“Whatever Gets You Thru the Night,” “Bring on the Lucie”) when they aren’t outright self-plagiarism (“Steel and Glass”). Each album has one great hit (“Mind Games” and “#9 Dream”) and simulations of something more (“Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out,” “Out the Blue”). Strong deep cuts (“One Day at a Time,” “What You Got”) are scarce and easy to miss. No one pretended Games was Imagine, and the best thing about Bridges was its promo tour, where a little Marxist (as in Groucho) wit and Hard Day’s Night vitality crept back into the old boy.

These records reveal how John couldn’t function without his in-absentia Madonna, and his heart already had that permanent hole in it — he could never release a career summary called Finally Enough Love. His empty cage now corroded (with liquor), it’s conceivable the solo John was already eyeing the exit on his lonely pop life three years in. But he was never gonna go down without a fight. So in between Mind Games and Walls and Bridges, he got the bright idea to rejuvenate his flagging spirit with a covers album of old singles he treasured, a popular move in ’73. And because obvious clinical insanity never deterred fiercely independent yet also parasitically codependent John, he hired the professional who’d improved Imagine as surely as he’d fucked up Ronnie Spector. Maybe that he’d gotten Phil to strip down for his debut LP gave him hope.

You’ve gotta love how every story of Phil Spector producing a record from this era on involves him firing a gun, and how there’s never any context for why — though there probably wasn’t any context for why. This episode inspired a top-shelf Lennon quip (“Phil, if you’re gonna kill me, kill me, but don’t fuck with my ears, I need ‘em!”) but little in the way of bullseye music. And anyway, John’s heart wasn’t exactly in it at the time either. The “rock oldies” idea was a canny and poignant, if somewhat regressive, move at that stage of his career. Yet Lennon came up with it under duress — Chuck Berry didn’t give a shit, but his publisher Morris Levy took umbrage with Lennon’s interpolation of lyrics from Berry’s (superior, but totally distinct) “You Can’t Catch Me” in “Come Together.” Suing a zillionaire: a temptation it takes mettle to dodge.

Here’s something you don’t hear when you play the best classic rock ‘n’ roll records, a number of which were subjected to Rock ‘n’ Roll’s revival — a shitload of unnecessary instruments. The most vulgar of these on Lennon’s LP is a mass of unavoidable horns compressed into a plastic dagger, like “Savoy Truffle” with less excuse. Lennon’s ‘70s solo music, which includes his fabulous if eccentric production for Nilsson’s Pussy Cats, is so special in part because it’s so idiosyncratic: Jim Keltner (if not Ringo) and Klaus Voormann beefed up into a pummeling bottom, horny-for-Elvis slapback on the vocal, guitars which never stop snarling. But there’s a dollop of decadent glitz on the Rock ‘n’ Roll tracks which shove its chestnuts through a Rocky Horror Show needle-eye, a rampant camp which smothers everything rough and spontaneous about the style.

What Lennon really needed to do was hire a true rock ‘n’ roll combo — surely, Scotty Moore and Bill Black would’ve turned up in a flash — replace Spector with someone other than himself, and, in a display of unprecedented discipline, shaped up his voice, to where he could’ve tempered the insecurities that always sent him rushing toward effects. There is simply no way this would have happened in 1973. Ergo, every cut on Rock ‘n’ Roll is like a game of What’s Wrong With This Picture. First thing you spot on the opener, Gene Vincent’s famously feral “Be Bop a Lula”, is a left-hand piano that couldn’t be less loose; second is a reverb you know he demanded be louder than his actual vocal input; third is the tragedy of hearing John throw away a classic his voice was designed for. File with “Rock ‘n’ Roll Music” under “unaccountable missteps”.

And then, for three glorious minutes, you wonder if maybe this’ll be a great record after all. Because Lennon’s take on Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me” is not only far better than the original, but one of the best recordings he ever made in his life. The original, though a gorgeous song held up by a powerful, casually soulful vocalist, was always a little too lilting and gossamer in its first Lieber-Stoller guise — typical for a Drifter, but inapposite for someone who’s insisting they’ll stand their ground. But for once on a busy record, those layers upon layers of instruments evoke high stakes, and Lennon sings like he’s fraying the end of his rope. Catching John when he really meant it in the ‘70s was trickier than bottling lightning. But this glorious recording did both.

Then a come tumble of well-intentioned mistakes — the most tight-a$’ed “Rip it Up” you’ve ever heard, which lassoes in “Ready Teddy” just so he can do two great songs dirty. A not-even-a-little-fleet-of-foot “You Can’t Catch Me,” with his voice fighting against, I dunno, the water metaphorically pouring into his waterlogged airmobile. A swingless “Ain’t That a Shame” he grinds to bits. Bobby Freeman’s batshit classic “Do You Wanna Dance” redone as the ugliest drunken Copacabana ballad. A “Sweet Little Sixteen” they should place on a neighborhood watch list. A “Slippin’ and Slidin’” that can’t get a few feet up the hill. A “Peggy Sue” whose rippling toms leave bruises. The least seductive Sam Cooke cover, ever mutating into a Little Richard tune even Rich’d consider too much (“whooooo! Ooh! mah soul, John. REEL it back! AAAAAOWW!”)

John is trying his ass off on most of these cuts, and he hadn’t sung this hard in ages. But his great trick used to be sounding desperate and flippant at the same time. Here he sounds strained, depressed, indifferent, indulgent, drugged-up, cracked-up, tin-eared, unmoored, unhinged and, under miles and miles of bravado (not to mention overdubs), totally unsure of himself. The degree to which he oversings this music he loves is so brutal it should’ve gotten him sued even more. You want to scrape off half of every arrangement — not so you can hear him, but so you can look him in the eyes and tell him to relax. Which he does once more, on a madly delectable cover of “Bony Moronie,” before he fleshes out the Lee Dorsey hit he’d dabbled in on Walls & Bridges (embarrassing his ever-neglected 11-year-old son Julian, who didn’t know the piano ‘n’ drums jam was being recorded) and drowns himself in a dolorous Lloyd Price ballad.

The engineers apparently caught degrees of decadence and depression from the old idol the public wouldn’t hear of until he got caught with a Kotex on his head. “John would drink a bottle of brandy or vodka a day,” May Pang told Peter Doggett. “I was so naïve at that time that I did not realize [he] was also on heroin.” Doggett reports that an outtake of the closing “Just Because” saw John commenting lasciviously on the assembled backing vocalists (“I want to suck your nipples, baby”), before emitting this deathless line: “I need some relief from my obligations. A little cocaine will set me on my feet.” Lennon was trapped in a nightmare even “I Am the Walrus” couldn’t match. That one was cut before the increasingly erratic Spector got in a car crash, in which he, among other injuries, lost his hair. The sessions went on indefinite hold.

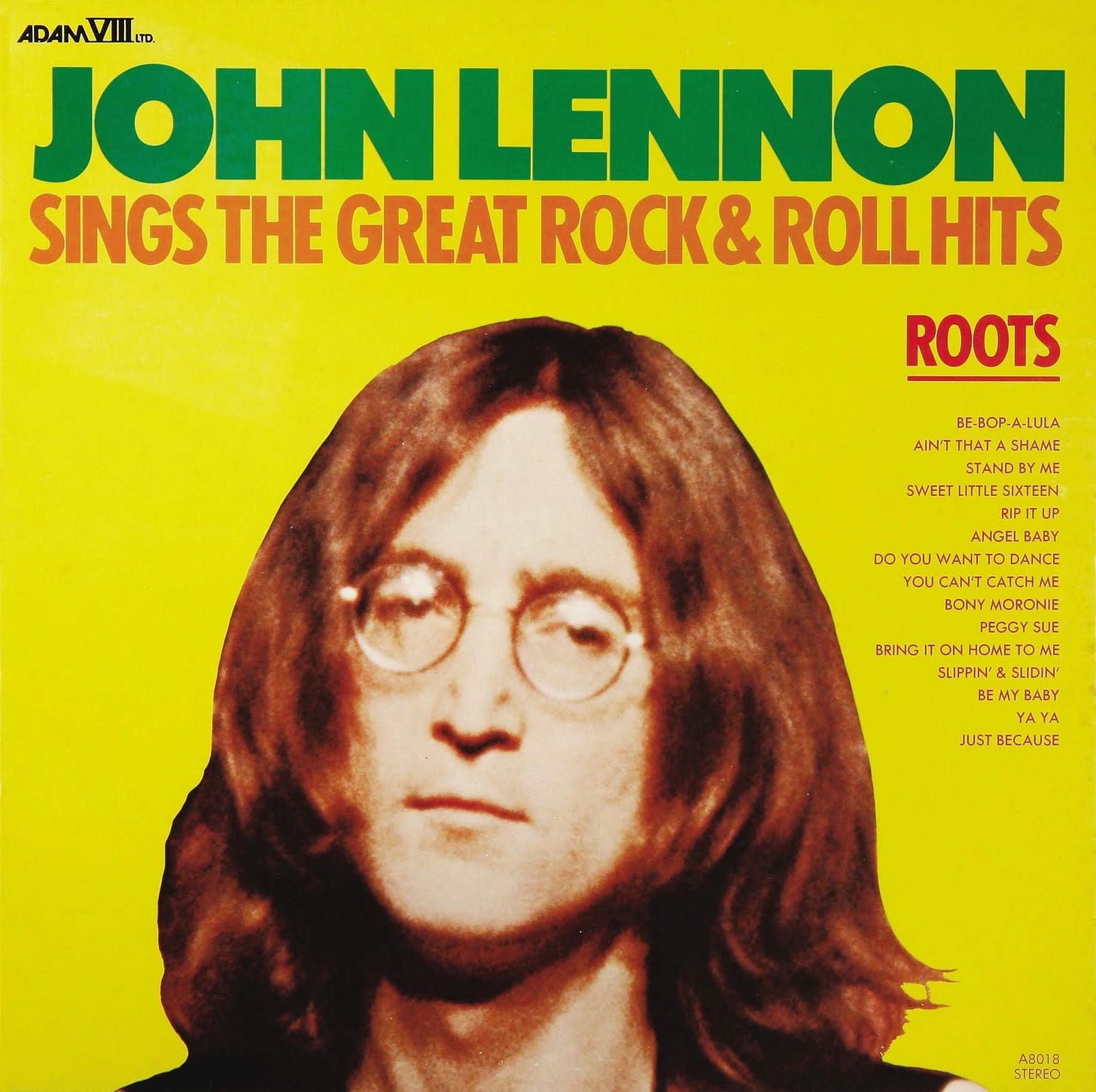

I’d love to manufacture dramatic prose out of the twists and turns in Lennon’s legal battle with Morris Levy as the LP came together (or didn’t). But I’ll leave that to all the lawyers and accountants who cherish his band enough to have pored over the forest-flooring documents Fab Four suits had piled up since Apple started to rot. The most absurd beat in the story was Levy calling John up in 1974, demanding to know what became of his score-settling covers project. Lennon tried to assuage him by sending over master tapes — which Levy then issued on his Adam VIII label as a cheapo mail-order LP called Roots: John Lennon Sings the Great Rock & Roll Hits. In a retread of the Alpha Omega-“red/blue” album kerfuffle, injunctions were filed, and Capitol rush-released Rock ‘n’ Roll in February ‘75, to keep fans from giving Levy any more dough.

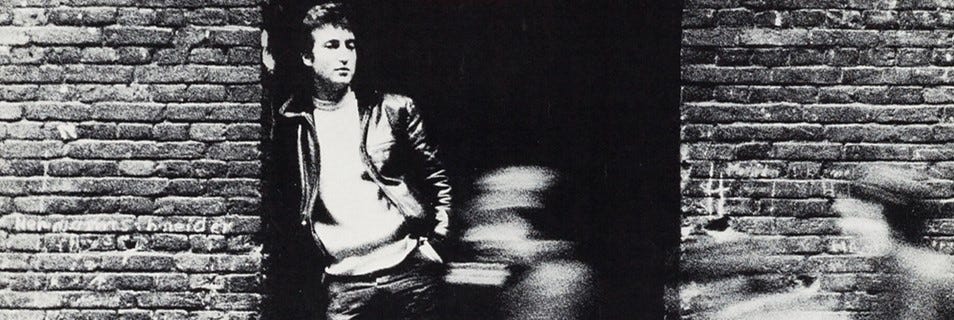

Many noted that the cover art, featuring Lennon as an unflappably cool-looking teddy boy (or, let’s be real here, punk) in the doorway of 22 Wohlwillstraße in Hamburg, was the best thing about the record — and outside of “Stand By Me” and “Bony Maronie,” it was. But like his earliest LPs, the concept was more valuable than the content. In going back to his roots, Lennon had discovered how many dead ends lay where he’d once found relief and release. The man who’d done more to rejuvenate rock ‘n’ roll in 1963 than anybody was tired in a way that cried for a change of direction. And either backstage at his spirited appearance with Elton John at Madison Square Garden, or some other place around that time, John was paid a visit by his all-time favorite guru, reaching out on the advice of a concerned Paul. A love story resumed being written.

At what cost, though? “The separation didn’t work out,” went another classic Lennon quip, but neither did a reunion he and three other old pals were acting more amenable to in late ’74, incidentally the year the quartet legally dissolved their partnership. John made public promises of new music around the time his taxing citizenship battle was finally resolved in early ‘75, but he mostly spent time repairing and reexploring bonds with Yoko. After Sean Lennon’s disquietingly difficult October 9 birth, a date John’s beautiful boy shared with his dad, the artist decided not to play those record industry mind games his three ex-bandmates would spend the second half of the ‘70s losing.

“Funnily enough, at the end of the Rock ‘n’ Roll [LP], on a track called ‘Just Because’, which Phil wanted me to sing… you hear me saying, ‘and so we say farewell from Record Plant West’. And something flashed through my mind as I said it — ‘am I really saying farewell to the business?’ It wasn’t conscious. And it was a long, long time before I did take time out. And I looked at the cover, which I’d chosen, which is a picture of me in Hamburg, first time we got there… So I thought, is this some kind of karmic thing? Here I am with this old picture of me in Hamburg from ‘61, and I’m saying ‘farewell from Record Plant’, and I’m ending as I started, singing this straight rock ‘n’ roll stuff.” — John Lennon to the BBC, December 6th, 1980

When John came back after years of casual demos and many, many loaves of bread, he felt and sounded like a new man, one who’d ascended more than a few rungs up the spiritual ladder. But the wildfire icon of the early ‘60s had flamed out years before.

Played it a couple of times again today.Not impressed the first time in the seventies.Now even less. Can't get the originals out of my head when i'm listening to it.But i can't say he didn't own that Speciality Records shit in his voice.Contrary to Costello's "Almost Blue".He can and could write Country songs,but that Country spirit was never in his voice to do such great songs some justice.Better his own songs on "King Of America"